This story is part of CBC Health's Second Opinion, a weekly analysis of health and medical science news emailed to subscribers on Saturday mornings. If you haven't subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here .

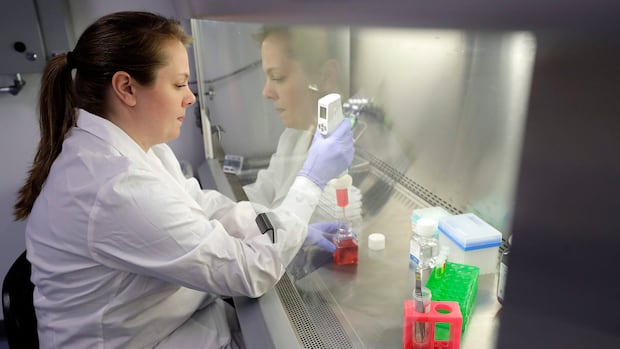

Cancer treatments don't always work as expected, leaving patients to suffer side effects of chemotherapy without gaining benefits. Now scientists are exploring whether tiny proxy organs made in the lab from a patient’s own cells can do a better job at predicting treatment success.

These proxy organs, also known as organoids, involve growing a patient’s cells into tissue that organizes itself.

In a more advanced technique, called an organ chip, the organoids are grown on a tiny 3D structure that simulates blood flow. The result? Lung tissue that expands and contract on its own or heart cells beating in unison.

Unlike testing drugs in conventional ways — like human cells growing flat in a dish, or testing on animals — organs on a chip can better capture the complexity of cancer growth and human functions to predict what pharmaceuticals will work safely, medical researchers say.

Here is some of their recent progress amid moves by regu

Continue Reading on CBC News

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.