“My name is Richard Robson. I’ve been at the University of Melbourne since 1966,” he says, with the casual precision of a man who has lived most of a life in one place. The image is homely and immediate: a long career, a kitchen table, a phone call.

Robson remembers the night the Nobel committee rang — “I did finish my fish. It was a bit cold, but I got there. And then I had to do the washing up,” he said — and the domestic detail does more than amuse. It pins an extraordinary moment to the ordinary rhythms that shaped it.

advertisement

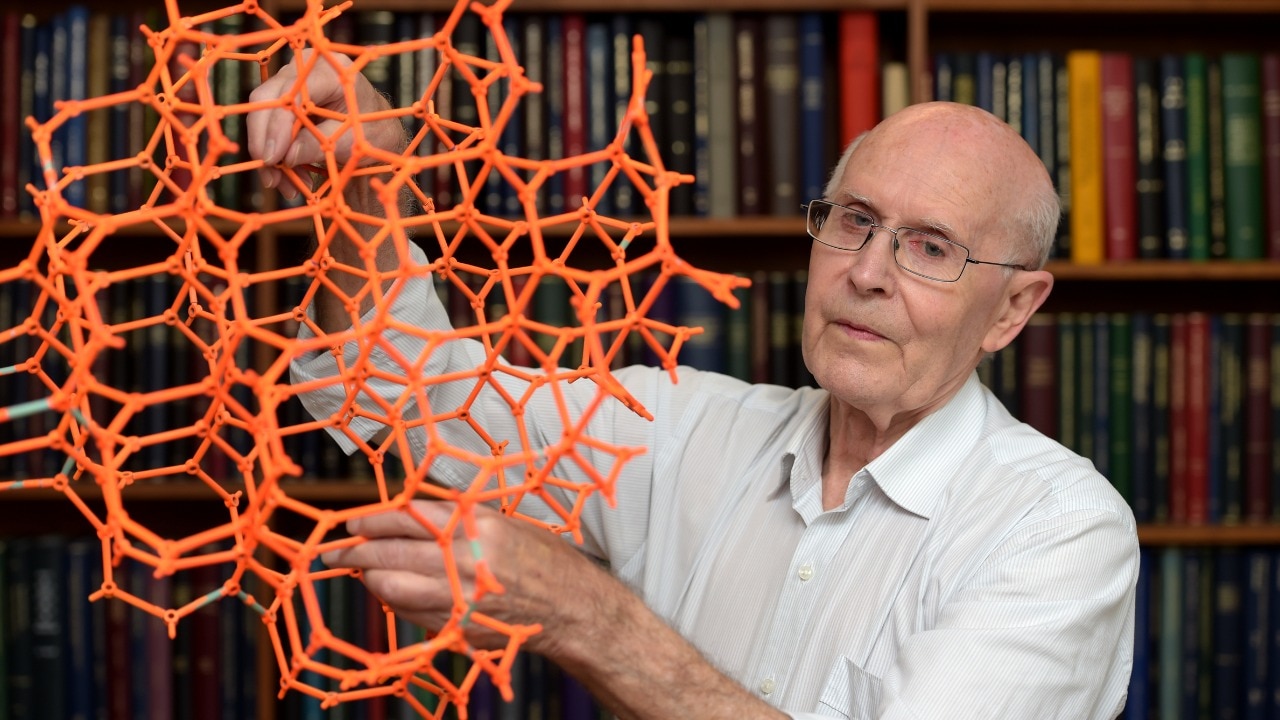

Robson shares the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Susumu Kitagawa and Omar M Yaghi “for the development of metal–organic frameworks” — a type of material built like a microscopic scaffold, with lots of empty space inside.

Imagine a building made of tiny corridors and rooms that only molecules can enter. By changing the parts used to build the scaffold, chemists can make the rooms act like traps, filters or tiny reaction chambers.

That flexibility is what makes these materials useful: they can hold gases, pull w

Continue Reading on India Today

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.