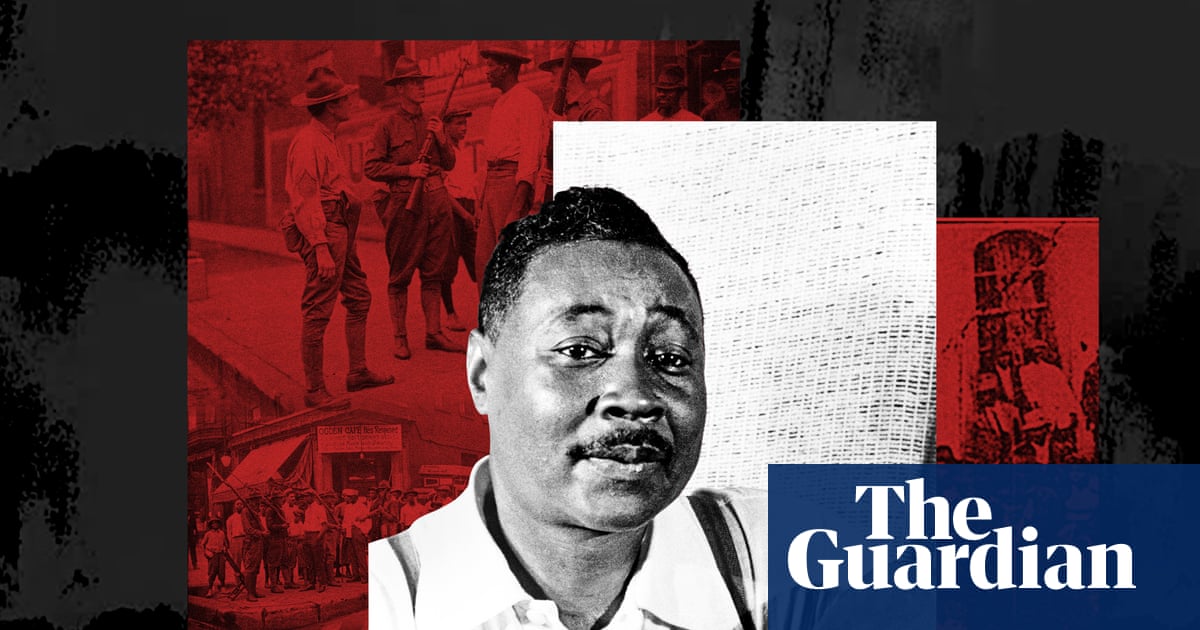

There was no greater vantage point to see America burn than the Pennsylvania railroad. Working in the summer of 1919 as a dining car waiter, Claude McKay was so fearful that he had resorted to travelling with a revolver secreted in his starched white jacket. During this volatile time, which became known as the US’s Red Summer, a wave of racial violence engulfed the country.

In a situation replicated across the western world, hundreds of thousands of first world war veterans had returned home and were now looking for work. Among them were Black troops who had fought for the allied powers and hoped that they would be awarded equal rights in return for their service. It was not to be.

Competition for labour and jobs would reveal ugly prejudices and trigger a prolonged spell of rioting and lynching across the US. Between April and November 1919, hundreds of people – most of them Black Americans – were killed and thousands injured. McKay, a 28-year-old Jamaican immigrant and aspiring poet, was shaken by the violence. “It was the first time I had ever come face to face with such manifest, implacable hate of my race, and my feelings were indescribable,” he later said. “I had heard of prejudice in America but never dreamed of it being so intensely bitter.”

The experience would prove formative to his writing. During the Red Summer riots, he wrote the impassioned sonnet If We Must Die. It was published in 1919 by the New York-based leftist publication the Liberator, which had been founded by Max Eastman and his sister, Crystal. The powerful verse, acknowledged by one contemporary as “the Marseillaise of the American Negro”, concluded with the lines, “Like men we’ll face the murderous, cowardly pack / Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!” It established McKay, who was living in Harlem at the time, as a literary talent and after it was reprinted in the major US Black newspapers and magazines of the time, McKay was lauded as “a poet of his people”.

The publication of If We Must Die marked the start of a lifelong collaboration between McKay and the Eastman siblings: the two would not just edit, publish and promote him, they would also provide him with financial support. Publication, however, brought unwelcome attention from the Justice Department’s committee investigating African American radicalism and sedition, which viewed the poem as inflammatory.

By the end of the summer, McKay had left his job on the railroad and started work in a factory in Manhattan, where he joined the revolutionary Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labour union. It is widely thought that pressure from the Justice Department led to McKay’s decision to leave the US in September 1919 and travel to the UK. However, he later stated that the spur was the offer from some of his literary admirers of an all-expenses trip, as well as his childhood desire to visit his “true cultural homeland”.

McKay discovered that reality did not match his ideal of “literary England”. He was disturbed to find that racial violence had followed him across the Atlantic. By the autumn of 1919, riots had taken place in London, Liverpool, Cardiff, Manchester and Hull. Five people were killed, dozens injured and at least 250 arrested. Further clashes took place in 1920 and 1921, triggered by competition for jobs and housing, but also by white hostility to mixed relationships. A Cardiff city police report stated: “There can be no doubt that the aggressors have been those belonging to the white race.”

According to the historian Jacqueline Jenkinson, the UK riots of 1919 emerged from the scorched earth of war: “At a time of stress, when xenophobia had become almost a way of life after over four years of constant German and anti-alien propaganda, those deemed ‘foreign’ by virtue of dark skin pigmentation were identified as legitimate targets for postwar grievances.”

Continue Reading on The Guardian

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.