To wait for a saviour is to inhabit a paradox — where passivity masks longing, and hope suspends time. This condition resists easy categorisation: it is neither purely mystical nor wholly political, neither naïve faith nor mere deferral. At its core lies a fundamental tension between the unbearable present and an imagined horizon — one that promises not just change, but transformation. This horizon may be divine or secular, collective or intimate, abstract or vividly embodied. The figure awaited may never arrive; yet the act of waiting continues to shape our dreams, define our silences, and haunt the thresholds of our becoming.

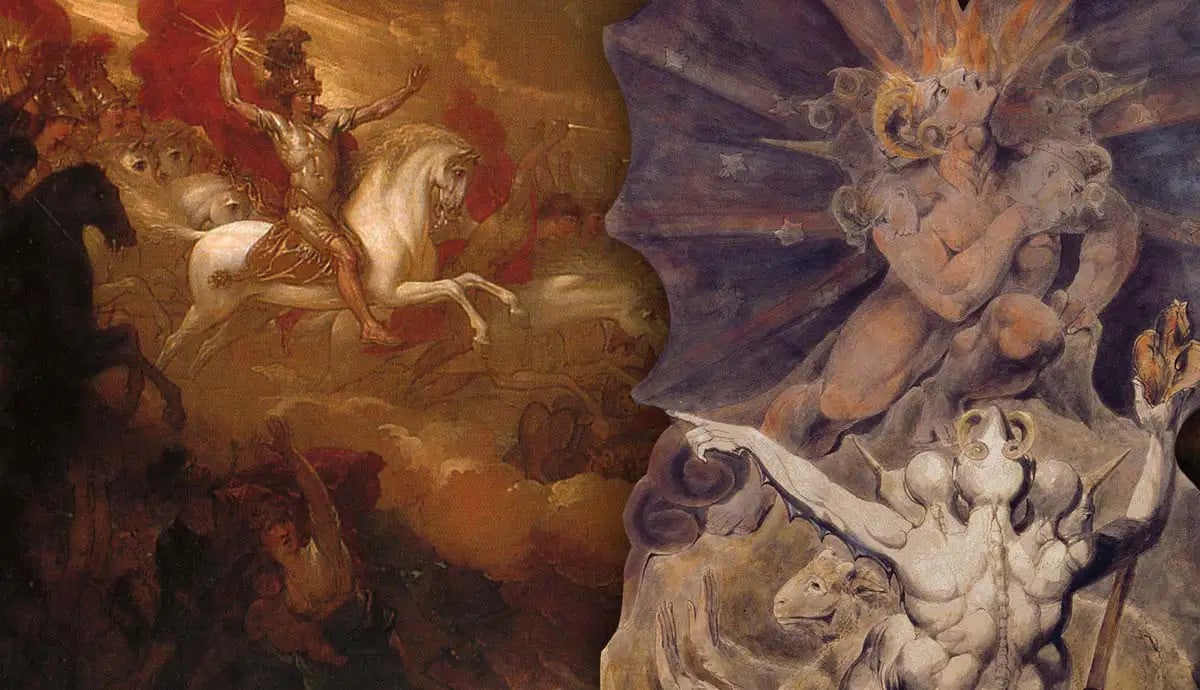

Walter Benjamin reminds us that “the Messiah comes not only as the redeemer, he comes as the subduer of Antichrist.” This duality — redeemer and destroyer — reveals the messianic figure as not just a bearer of peace, but a force of historical rupture. Benjamin further warns that even “the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he wins,” insisting that the task of hope is as much about redeeming the past as anticipating the future. Franz Kafka, with his paradoxical clarity, wrote: “The Messiah will come only when he is no longer necessary... on the very last day.” This deferral of arrival mirrors the way hope often remains just beyond reach. Yet Ernst Bloch distinguished between false hope that enervates and “concretely genuine hope” that fortifies the soul. And perhaps Che Guevara captured the ethical charge of such hope in its most radical form when he exhorted: “Be realistic, demand the impossible!”

Such waiting, then, is not a singular or static experience — it emerges from a web of human needs, histories, and narratives. Beneath its various forms lies a layered architecture of emotion, ideology, and belief. These dimensions may differ in their source or articulation, but they are all animated by the same inner

Continue Reading on The Express Tribune

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.