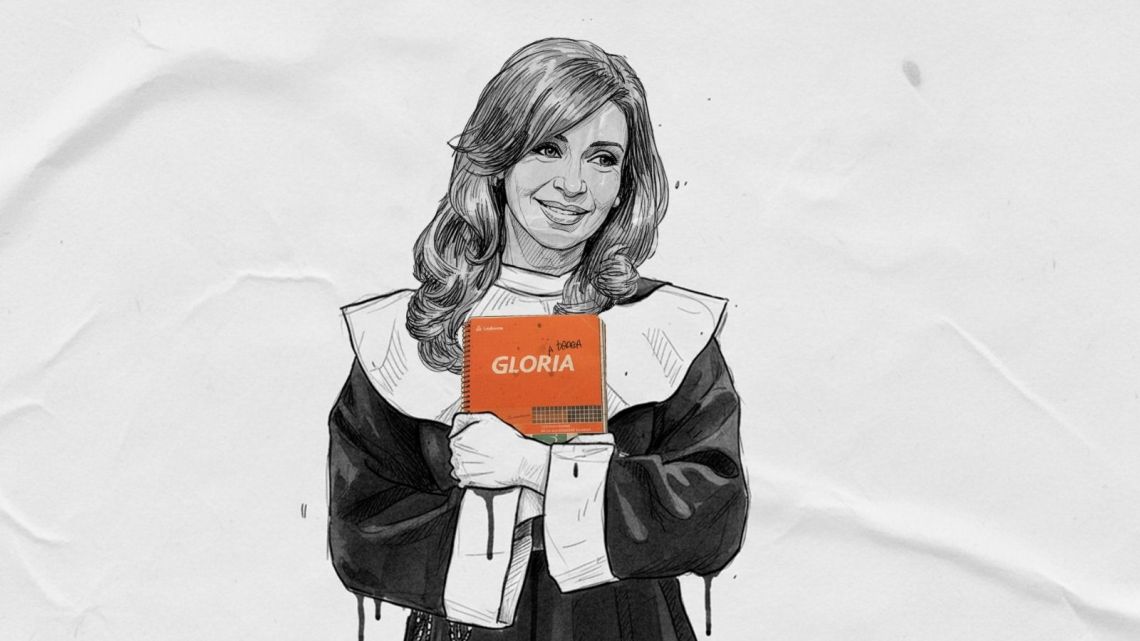

The ‘Cuadernos de las coimas’ corruption notebooks case digs up one of the deepest dilemmas facing Argentine politics. How much of the undeclared money raised was for electoral campaigns under the table, a practice followed by all political parties, and how much fell by the wayside for government officials and then-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner herself? In an interview with Modo Fontevecchia this week, Diego Cabot – the journalist who first denounced this case – said that many Kirchnerite officials live without working after leaving office, thanks to cash that they vulgarly call money “for politics.”

With evidence including registered manuscripts, the confessions of businesspeople and the testimony of whistleblowers, the case looks solid beyond the denunciations facing late federal judge Claudio Bonadio, who initiated the case, and his animosity for Fernández de Kirchner. It has been discussed whether the concept of whistleblower has been abused, with businessmen allegedly scared into delivering the desired testimony, but much of what they declared was later confirmed by forensic experts who used geolocation software to pinpoint their mobile telephones at the places indicated by the alleged records in the notebooks, along with suspicious bank movements prior to the delivery of bags of cash.

This is for sure one of the most iconic cases of political corruption in recent Argentine history. Regarding the responsibility of the ex-president, who is already convicted in another graft case and serving jail time under house arrest, it has been argued that she could not be unaware. In the Cuadernos case, the relationship between the facts and her person is even greater because bags of money allegedly went to her own home. If the money was “to fund politics” and not for her personal benefit, it should be pointed out that it is still a crime all the same and, at the very least, she is responsible for not having prevented it.

The philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas maintained that all legitimate power should be oriented to the common good. When rulers act to their own benefit, whether in the singular or in plural, and not the people, they become tyrants. In that case, obedience ceases to be a virtue and the citizen acquires a moral responsibility – they cannot remain passive in the face of injustice.

Continue Reading on Buenos Aires Times

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.