When the American republic was founded, the Earth was no more than 75,000 years old. No contemporary thinker imagined it could possibly be older. Thus Thomas Jefferson was confident that woolly mammoths must still live in “the northern and western parts of America,” places that “still remain in their aboriginal state, unexplored and undisturbed by us.”

The idea that mammoths or any other kind of creature might have ceased to exist was, to him, inconceivable. “Such is the œconomy of nature,” he wrote in Notes on the State of Virginia, “that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; of her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken.”

Explore the November 2025 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

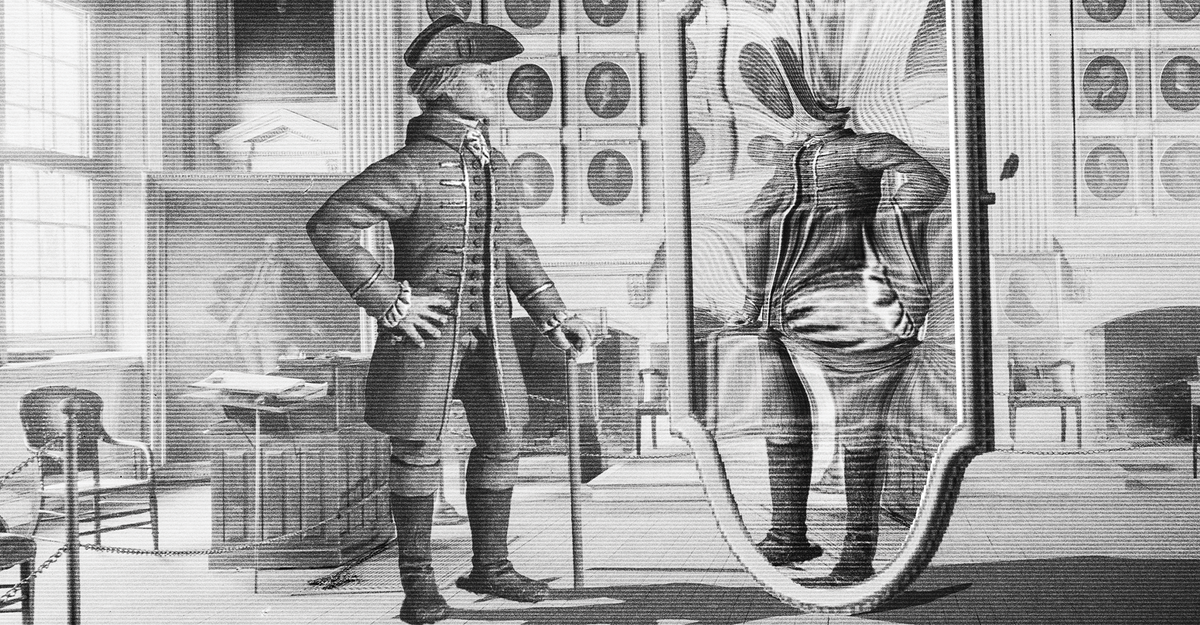

Those illusory behemoths roaming out there somewhere beyond the Rockies remind us that the world of the Founding Fathers is in some ways as alien to us as ours would be to them. A distance of two and a half centuries is too long for us to be able to fully inhabit their universe, but not long enough for us to be capable of viewing them disinterestedly or dispassionately. In trying to imagine how they would perceive the state of their republic in 2025, the risk is that we invent our own versions of Jefferson’s nonexistent beasts. The originalist fallacy that dominates the current Supreme Court—the pretense that it is possible to read the minds of the Founders and discern what they “really” meant—in fact turns the Founders into ventriloquists’ dummies. We express our own prejudices by moving their lips.

From the October 2025 issue: Jill Lepore on how originalism killed the Constitution

Yet asking what the Revolutionary leaders would think of America now has long been a spur to critical thinking. The interrogation of how well or badly the present condition of the nation matches the founding intentions is one of the vital forces behind the American political project. It kindles the fire that blazes in Frederick Douglass’s Fourth of July speech of 1852, during which he said of the Founders that their “solid manhood stands out the more as we contrast it with these degenerate times.” It is the test Abraham Lincoln presents in the Gettysburg Address: whether the form of republican government created “four score and seven years ago” by “our fathers” might be about to “perish from the earth.” It underpins Martin Luther King Jr.’s resplendent rebuke at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963: “When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir.”

We do not have to sanitize the Founders into secular sainthood to ask what their republic has done with that legacy. We can use their magnificent words to reproach many of America’s contemporary follies even while recognizing that some of their actions prefigure those follies. It is quite possible, for example, that many of the Founders might be enthusiastic supporters of Donald Trump’s unilateral imposition of swinging tariffs on foreign trade—albeit not of the bellicose rhetoric that accompanies them. In 1807, Congress, with Jefferson as president and James Madison as secretary of state, prohibited cargo-bearing American vessels from sailing to foreign ports and forbade the export of all goods out of the country by sea; imports also declined, largely because it was impractical for ships from abroad to make the trip if they had to return empty.

From the September 2003 issue: Our reverence for

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.