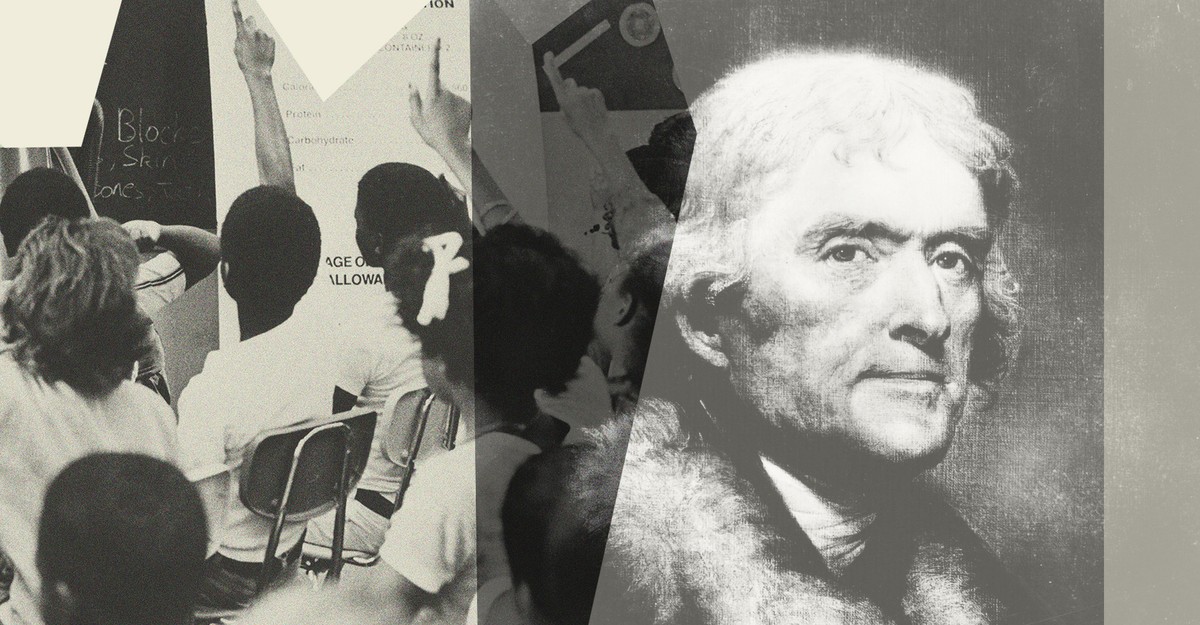

“Raise your hand if you’ve heard of Thomas Jefferson,” I said to a group of about 70 middle schoolers in Memphis. Hands shot up across the auditorium. “What do we know about him?” I asked.

“He was the president!” one said.

“He had funny hair!” said another.

“He wrote the Constitution?” one remarked, half-asking, half-asserting.

I responded to each of their comments:

“Yes, he was our country’s third president.”

“That’s actually how many men wore their hair back then. Many men even wore wigs.”

“Close! He was the primary writer of the Declaration of Independence.”

Then I asked, “Did you know that Thomas Jefferson owned hundreds of enslaved Black people?” Most of the students shook their heads. “What if I told you that some of those people he enslaved were his own children?” The students gasped.

Recently, I visited schools in Virginia, Tennessee, Georgia, Louisiana, and South Carolina, all states where legislators have passed laws and implemented executive orders restricting the teaching of so-called critical race theory. I was on tour to promote the newly released young readers’ edition, co-written with Sonja Cherry-Paul, of my 2021 book, How the Word Is Passed, which is about how slavery is remembered across America.

I began most of my school presentations with a similar exchange about Jefferson because, even today, millions of Americans have never been taught that the Founding Father was an enslaver, let alone that Sally Hemings, an enslaved woman, gave birth to at least six of Jefferson’s children (beginning when

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.