The first idea of a genuine talking-machine appears to belong to Thomas A. Edison, who, in 1875, took out patents upon a device intended to reproduce complex sounds, such as those of the human voice. Of the thousands of persons who in that year visited the small room in the Tribune building, in New York, where the first phonograph was for months on exhibition, very few were found to hope much for the invention. It was apparently a toy of no practical value; its talking was more or less of a caricature upon the human voice, and only when one knew what had been said to the phonograph could its version be understood.

Edison’s early phonograph nevertheless contained every essential feature of the new instruments which he and other inventors are about to introduce. It was founded upon the discovery that if a delicate diaphragm or sounding-board is provided with a sharp point of steel, its vibrations under the sound of the human voice will cause the sharp point or stylus to make a series of impressions or indentations upon a sheet of wax or other material passed beneath it. Such indentations, though microscopic, are sufficiently defined to cause similar vibrations in the diaphragm, if the stylus is again passed over the furrow of indentations, and this reproduction is loud enough to be heard.

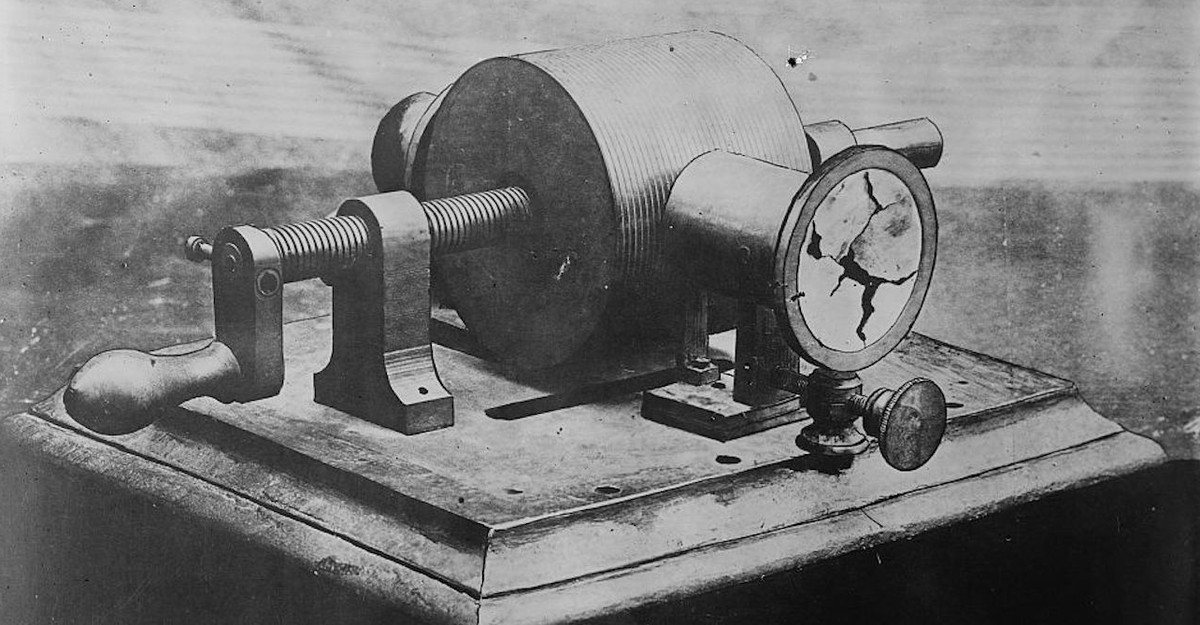

Thus the phonograph in its rudest form consists of a little sounding-board, carrying on its under side a needle-point, and a sheet of wax so held as just to touch the needle. The sound waves of the voice cause the sounding-board with its needle-point to vibrate with a rapidity varying with the pitch of the note. If the wax sheet is moved slowly along while talk is going on, the result is a line of minute indentations. So far there is nothing surprising about the apparatus. But at the end of a line across the wax sheet raise the diaphragm, and put it back to the beginning of the line, causing the point to travel again over the same line of indentations. Listen carefully, and a repetition of the original sounds spoken or sung into the apparatus will be heard, strong or weak, distinct or indistinct, according to the perfection of the instrument. Tin-foil sheets were first used to receive the impression; they were placed on a cylinder, which was turned slowly by hand, in front of the vibrating diaphragm. While the cylinder carrying the foil had a rotary motion, it also moved from right to left, so that the line of dots or indentations made by the stylus formed a spiral running around the cylin

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.