When Vladimir Putin met with Donald Trump in Alaska in August, one prominent strand of social-media commentary had nothing to do with the possibility of a deal to end Russia’s war against Ukraine (the meeting’s ostensible purpose). Rather, it turned on the question of whether Putin—who faces an arrest warrant issued by the International Criminal Court, stemming from Russia’s wartime actions—could conceivably be arrested when he stepped foot on U.S. soil.

As a practical matter, of course, the answer was no—it wouldn’t happen, and not just because the Trump administration had no interest in making an arrest, or because the Russian reaction would be dangerous, or because the United States is not a member of the ICC. As a legal matter, most countries treat a serving national leader—a president, a prime minister, a king; whether its own or that of some other country—as having complete immunity from the jurisdiction of their national courts. Immunity is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary as an “exemption” from the duties and liabilities imposed by the law. A serving national leader with personal immunity cannot be arrested, detained, or judged.

But what happens after a national leader has left office? And what if he or she is accused of having committed crimes under international law while in office, such as torture or genocide? Can a former national leader ever be arrested by another country and judged by its courts for crimes committed elsewhere while in office?

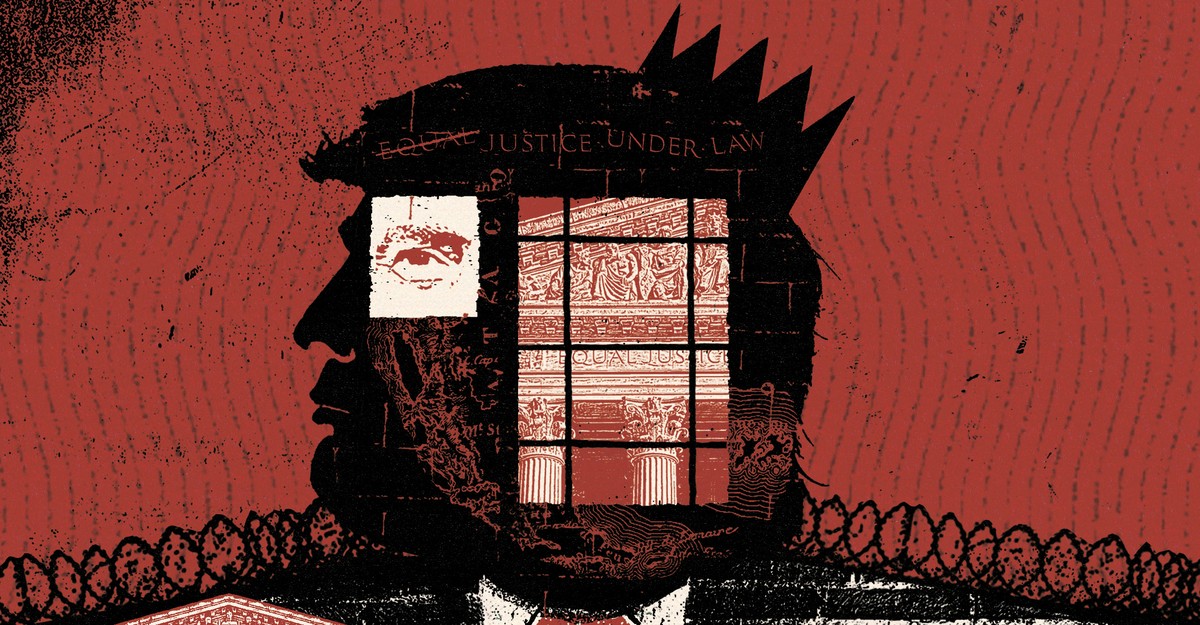

Read: The Supreme Court goes through the looking glass on presidential immunity

The answer to that question is yes, or at least it has been: In recent decades, the vector of legal evolution has pulled international jurisprudence away from blanket immunity. To my mind, as an international lawyer who has been involved in cases dealing with international crimes, this is the right direction.

But images of the summit meeting in Alaska brought international law once again to the fore, and offered a reminder that the international legal regime is under threat. The reason relates not so much to Putin as to Trump. Specifically, the Supreme Court’s 2024 ruling in Trump v. United States—an immunity case that concerned a former president’s legal liability for actions in relation to official conduct—could have potentially far-reaching ramifications for international justice.

The idea that criminal law is applicable to any person—even a king or a president—is not new. In 1649, King Charles I was put on trial for a “wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people.” Convicted, he paid with his head.

In 1764, the Italian jurist Cesare Beccaria offered a rationale for the idea that the criminal law should extend to rulers and why criminal sanctions should apply globally: “The certainty of there being no part of the earth where crimes are not punished may be a means of preventing them.”

That said, for centuries the rule was clear: A foreign head of state could never be subject to the jurisdiction of another country’s courts, either while in office or subsequently, in relation to official conduct. The immunity from prosecution was absolute. The U.S. Constitution, which came into force in 1789, makes no mention of immunity for the U.S. president, either while in office or afterward. But in 1812, the Supreme Court recognized that a serving foreign head of state had absolute immunity while present on American soil. It said nothing in that decision about immunity from criminal prosecution for the president.

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.