On the whole, the Founding Fathers, those towering patriarchs, fared poorly when it came to sons. George Washington and James Madison had none. Thomas Jefferson’s only legitimate one died in infancy. Samuel Adams also outlived his. With the exception of John Quincy Adams, no other son of a Founder rose to his father’s stature. The unluckiest of all may have been Benjamin Franklin, who, in the course of a deeply familial contest, lost a cherished son the hardheaded way: to politics.

Explore the November 2025 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

The two were for years each other’s closest confidant. As one associate noted, William Franklin had, by his late 20s, become his father’s “friend, his brother, his intimate and easy companion.” Franklin raised his son with all the advantages he had not enjoyed. Where he had only briefly attended school, William studied with a private tutor. He kept a pony. He signed no indenture papers.

Similarities surfaced early. Around the time he turned 15, William ran off to join the crew of a ship docked in Philadelphia, from which his father retrieved him. Franklin could hardly argue with the dash for freedom, having made his own at 17. He too had longed, as a youth, for the sea. Shortly after his escapade, William was allowed to enlist in the British army. The concession seemed to affirm that he in no way suffered from the brand of “harsh and tyrannical treatment” that Franklin had known as a boy, treatment he thought might explain his later aversion to arbitrary power. He was, and knew he was, an indulgent parent. He once counseled a friend to give a child all he wanted, so that the child would develop a pleasant countenance. William was exceedingly handsome.

William’s military career ended in 1748, with the conclusion of King George’s War. While studying law, he over the next few years stepped into a string of political posts as his father vacated them. Father and son joined the same clubs and supported the same charities. They performed electrical experiments together and campaigned for office together. They were nearly shipwrecked together when, in 1757, they sailed to London, where together they visited the British Museum and watched David Garrick play Hamlet. (A fiancée of whom Franklin disapproved was left behind, soon forgotten by William.) William made business calls on his father’s behalf when Franklin found himself confined, by a months-long illness, to bed. He took his dictation. Oxford conferred an honorary doctorate on Franklin in 1762 for his electrical discoveries. Farther back in the same procession marched William, then in his early 30s, who received a master’s degree.

Read: Ben Franklin’s radical theory of happiness

Deeply grateful for his father’s “numberless indulgencies,” William in 1758 professed himself willing to follow him to America, or to go to “any other part of the world, whenever you think it necessary,” and he did. The two traveled around the British Isles and to the continent, from which they returned in time for the 1761 coronation of George III. (William alone obtained a special ticket that allowed him to join the procession, all the way into Westminster Abbey.) They visited Northamptonshire, where Franklin filled in some blanks in the family history. He returned to that visit later when he began his Autobiography, which masquerades as a letter to William.

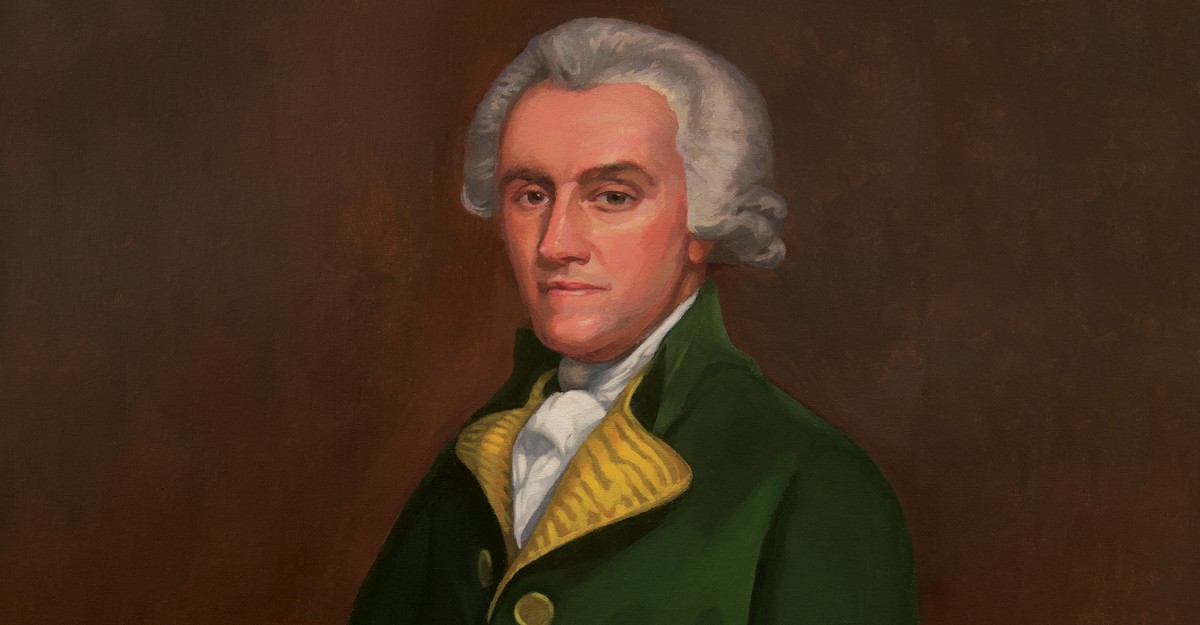

Illustration by Maggie O’Keefe

Friends commented on how much the two men resembled each other in manner and bearing. There could be no tributes to the other side of the family; it was common knowledge in Philadelphia that Franklin’s wife was not William’s mother. If William knew her name, he was among the few who did. For all intents and purposes, he seemed to have been the love child of Ben Franklin and Poor Richard. His mother’s identity frustrates us as much today as it did the 18th-century gossips, who turned her—especially in the thick of an election season—into an abused handmaid or oysterwoman, left by Franklin to beg in the streets. She was likely a household servant for whom Franklin provided, having arranged to raise their son himself.

The stain of William’s birth reared its head in London only when—at a surprisingly early age—he wa

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.