“It’s not true that no one needs you anymore.”

These words came from an elderly woman sitting behind me on a late-night flight from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C. The plane was dark and quiet. A man I assumed to be her husband murmured almost inaudibly in response, something to the effect of “I wish I was dead.”

Again, the woman: “Oh, stop saying that.”

I didn’t mean to eavesdrop, but couldn’t help it. I listened with morbid fascination, forming an image of the man in my head as they talked. I imagined someone who had worked hard all his life in relative obscurity, someone with unfulfilled dreams—perhaps of the degree he never attained, the career he never pursued, the company he never started.

At the end of the flight, as the lights switched on, I finally got a look at the desolate man. I was shocked. I recognized him—he was, and still is, world-famous. Then in his mid‑80s, he was beloved as a hero for his courage, patriotism, and accomplishments many decades ago.

As he walked up the aisle of the plane behind me, other passengers greeted him with veneration. Standing at the door of the cockpit, the pilot stopped him and said, “Sir, I have admired you since I was a little boy.” The older man—apparently wishing for death just a few minutes earlier—beamed with pride at the recognition of his past glories.

For selfish reasons, I couldn’t get the cognitive dissonance of that scene out of my mind. It was the summer of 2015, shortly after my 51st birthday. I was not world-famous like the man on the plane, but my professional life was going very well. I was the president of a flourishing Washington think tank, the American Enterprise Institute. I had written some best-selling books. People came to my speeches. My columns were published in The New York Times.

But I had started to wonder: Can I really keep this going? I work like a maniac. But even if I stayed at it 12 hours a day, seven days a week, at some point my career would slow and stop. And when it did, what then? Would I one day be looking back wistfully and wishing I were dead? Was there anything I could do, starting now, to give myself a shot at avoiding misery—and maybe even achieve happiness—when the music inevitably stops?

Derek Thompson: Workism is making Americans miserable

Though these questions were personal, I decided to approach them as the social scientist I am, treating them as a research project. It felt unnatural—like a surgeon taking out his own appendix. But I plunged ahead, and for the past four years, I have been on a quest to figure out how to turn my eventual professional decline from a matter of dread into an opportunity for progress.

Here’s what I’ve found.

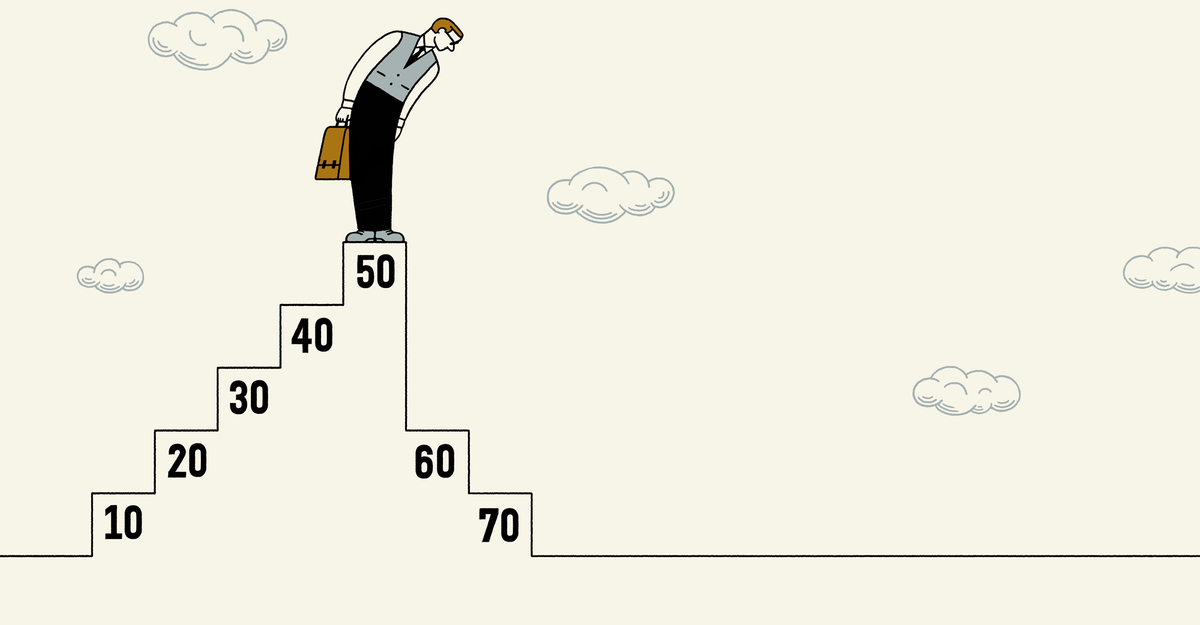

The field of “happiness studies” has boomed over the past two decades, and a consensus has developed about well-being as we advance through life. In The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After 50, Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution scholar and an Atlantic contributing editor, reviews the strong evidence suggesting that the happiness of most adults declines through their 30s and 40s, then bottoms out in their early 50s. Nothing about this pattern is set in stone, of course. But the data seem eerily consistent with my experience: My 40s and early 50s were not an especially happy period of my life, notwithstanding my professional fortunes.

From December 2014: Jonathan Rauch on the real roots of midlife crisis

So what can people expect after that, based on the data? The news is mixed. Almost all studies of happiness over the life span show that, in wealthier countries, most people’s contentment starts to increase again in their 50s, until age 70 or so. That is where things get less predictable, however. After 70, some people stay steady in happiness; others get happier until death. Others—men in particular—see their happiness plummet. Indeed, depression and suicide rates for men increase after age 75.

Luci Gutiérrez

This last group would seem to include the hero on the plane. A few researchers have looked at this cohort to understand what drives their unhappiness. It is, in a word, irrelevance. In 2007, a team of academic researchers at UCLA and Princeton analyzed data on more than 1,000 older adults. Their findings, published in the Journal of Gerontology, showed that senior citizens who rarely or never “felt useful” were nearly three times as likely as those who frequently felt useful to develop a mild disability, and were more than three times as likely to have died during the course of the study.

One might think that gifted and accomplished people, such as the man on the plane, would be less susceptible than others to this sense of irrelevance; after all, accomplishment is a well-documented source of happiness. If current accomplishment brings happiness, then shouldn’t the memory of that accomplishment provide some happiness as well?

Maybe not. Though the literature on this question is sparse, giftedness and achievements early in life do not appear to provide an insurance policy against suffering later on. In 1999, Carole Holahan and Charles Holahan, psychologists at the University of Texas, published an influential paper in The International Journal of Aging and Human Development that looked at hundreds of older adults who early in life had been identified as highly gifted. The Holahans’ conclusion: “Learning at a younger age of membership in a study of intellectual giftedness was related to … less favorable psychological well-being at age eighty.”

Explore the July 2019 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

This study may simply be showing that it’s hard to live up to high expectations, and that telling your kid she is a genius is not necessarily good parenting. (The Holahans surmise that the children identified as gifted might have made intellectual ability more central to their self-appraisal, creating “unrealistic expectations for success” a

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.