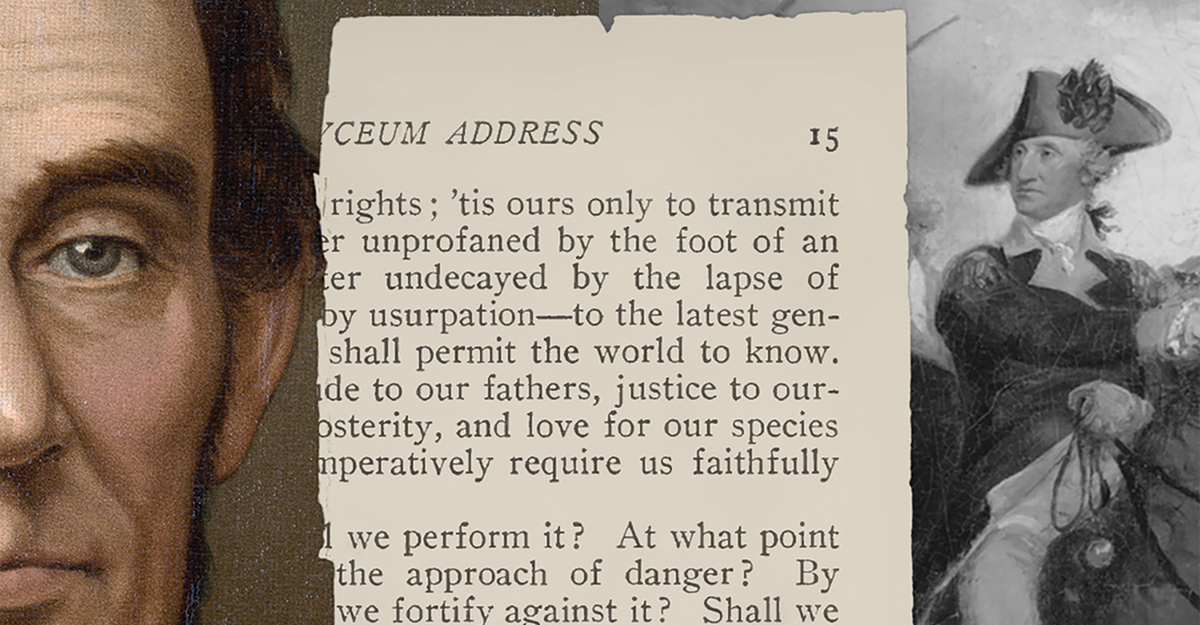

Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address is a dense, technical affair. Delivered in March 1861, before the outbreak of the Civil War but after seven states had left the Union, it could hardly have been the occasion for much else. After a long treatise on the illegality of secession, Lincoln closed with a single flourish. His plea to the “better angels of our nature” is so familiar that we can miss the very particular intercession he imagines. The better angels will touch “the mystic chords of memory” reaching “from every battle-field, and patriot grave” into the hearts of all Americans and “yet swell the chorus of the union.” It is a complex, orchestral vision: angels as musicians, shared past as instrument, the nation itself stirred back into tune.

Explore the November 2025 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

We can still hear in Lincoln’s final, lyrical turn something of what the American Revolution sounded like in his head: transcendent and alive. With good reason, he believed the same to be true for other Americans. They, too, had been reared in a culture of deep veneration for the Revolutionary past; they, too, had heard the stories, memorized the speeches, attended the parades, and worshipped “the fathers.” The problem was that he saw himself as the protector of the Revolution, while those who formed the Confederacy claimed to be its rightful heirs. What he called “the momentous issue of civil war” could not be averted.

On the verge of 250 years from 1776, the mystic chords of memory are badly out of tune, the better angels nowhere to be seen. The Revolution does not live for us in the same way it did for Lincoln. Its remains lie dry and brittle, ready fuel for culture-war conflagration. We are caught between caricatured versions of the Revolutionary past. One presents the Founders as hypocrites who could do no right; the other casts them as heroes who could do no wrong. The first forecloses the possibility of a collective and usable past; the second locks us into a limited vision of who we are based on who we were.

We would do well to hear something of Lincoln’s Revolution in our own heads. Lincoln rose to prominence at a moment of crisis, when the legacy of the Revolution was at stake. He did not shy away from what he called “the monstrous injustice” of slavery—and he certainly did not seek to

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.