Washington Irving was born just as the news reached New York City: The war with England was over. To celebrate, his mother named him after the victorious American general. When he was a boy of 6, Irving was out for a walk with a Scottish maidservant, who spotted George Washington, now the nation’s first president, on a Manhattan street. The enterprising maidservant followed him into a shop. (Apparently, presidents once ran their own errands.) “Please, Your Honor,” she said. “Here’s a bairn was named after you.” Putting his hand on the young man’s head, Washington bestowed his blessing.

Explore the November 2025 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

Thus anointed, Irving went on to become America’s original literary celebrity. During the first half of the 19th century, Charles Dudley Warner wrote in The Atlantic in 1880, “probably no citizen of the republic, except the Father of his Country, had so wide a reputation as his namesake, Washington Irving.” Irving wrote one of the first, and still one of the best, American ghost stories: “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” about a Hessian soldier who lost his head to a Patriot cannonball. He wrote satirical sketches, romantic tales, travelogues, and, near the end of his life, a five-volume biography of George Washington.

Yet the story that established Irving’s literary reputation is, at first glance, not a likely one to build a new national literature around. Irving wrote it during a sojourn in Britain. He took its bones from a German folktale. And although set in the Revolutionary era, the story doesn’t dramatize America’s fight for independence. Rather, the protagonist dozes right through it.

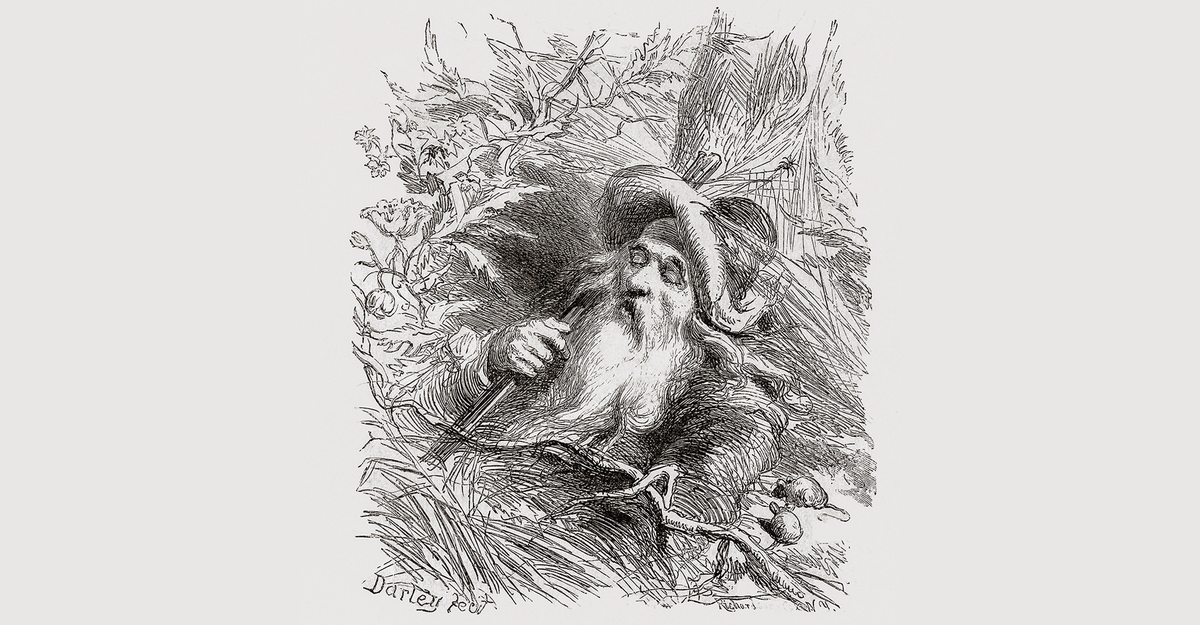

“Rip Van Winkle” is one of those stories that is at once familiar and obscure. Its contours remain well known: Man takes long nap, grows very long beard, returns to changed world. Its hero has become shorthand, to the point of cliché, to describe any long slumber. Yet Irving’s short story is not as widely anthologized or read as it once was. Its complexities and peculiarities are only dimly recalled, if at all, by many readers.

That is a shame, because unlike a lot of antique American writing, “Rip Van Winkle” has retained much of its original appeal. Mark Twain famously accused Irving’s contemporary James Fenimore Cooper of committing 114 of a possible 115 literary offenses on a singl

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.