I

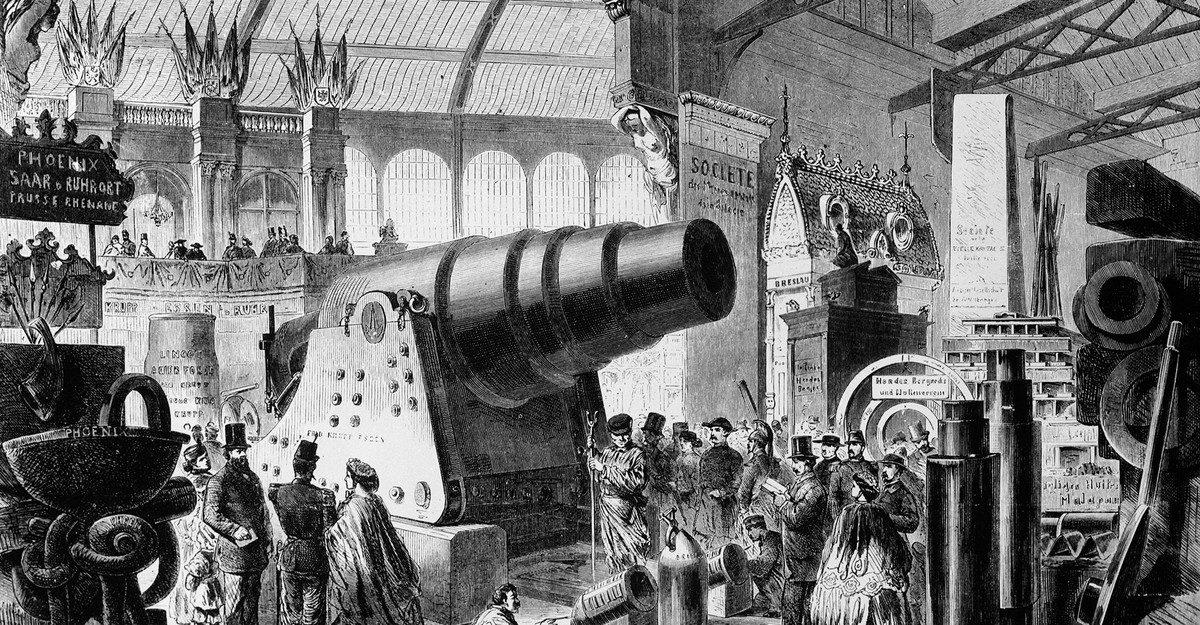

IN 1867, at the International Exhibition in the Champ de Mars, Paris, appreciative judges awarded a prize to the biggest and deadliest gun manufactured by the ‘Cannon King,’ Alfred Krupp. Three years later, France had practical, if painful, proof that her award was well merited. Half a century later, this gun’s successors — notably the mysterious ‘Big Bertha,’ which had a radius of seventy-five miles, which killed seventy-five noncombatants on Good Friday in the church of St. Gervais, and w hich disappeared as easily as a toy pistol after the signing of the Armistice— showed conclusively that prizes, like chickens and curses, come home to roost.

The reaction after the World War has temporarily dimmed mankind’s interest in guns, and concentrated it upon plans for peace. True, a brigadier general of the United States army has recently carried away from English competitors a British War Office prize of three thousand pounds for a selfloading rifle, which can fire twice as fast as a hand-loaded rifle, and can therefore be trusted to kill twice as many people. But this is an unusual, though widely heralded, event. For the most part, prize givers and prize winners are substituting the abstract for the concrete, the desired for the ascertained. It is the natural and touching belief of reformers (every American, says André Siegfried, is at heart an evangelist) that by putting up enough money they can ensure reform. The mediæval barons had a somewhat similar set of convictions, though the goal they sought was different. It took the wisdom of an unlettered peasant to enunciate the great truth: ‘Le bon Dieu ne vend pas ses biens.’

The connection between Colonel Charles Lindbergh’s Latin American flights and permanent — or even temporary — peace is hard to trace; but we can all sympathize with the relief of the Woodrow Wilson Foundation when Heaven sent its way this splendid young adventurer to whom it could give the award. Awards, especially recurrent awards, are a weighty obligation. Something has to be done with them, and the supply of prize money is occasionally in excess of legitimate demands. Colonel Lindbergh is one of the outstanding figures of the world to-day. He has made history as history has always been made, by men who go about their life’s work with no great regard for spectators. That he should receive the Woodrow Wilson award pleased the public, and made possible some charming phrases, such as ‘healing wings,’ and ‘the young ambassador of good will.’ If international relat ions rested upon sentiment or phraseology, the Western continent would be a love nest.

It may be remembered that thirtyseven years ago Oscar Wilde — a keen pacifist — was convinced that, although emotional sympathy would never be strong enough to unite civilized nations, intellectual sympathy might accomplish this great end. ‘It would give us the peace which springs from understanding.’ He felt sure, for example, that no Englishman who was capable of appreciating the excellence of French prose would ever want to make war on France, which may or may not be true. Germany, having an avowed preference for stodgy prose, was naturally immune from such an influence. Goethe, whom Mr. Wilde quoted with triumph, did indeed confess that, in his eyes, the culture of France outweighed her belligerence; but no general argument can rest on such a foundation. A world of Goethes would be a world at peace.

II

The ineradicable buoyancy of the human heart, and the ineradicable materialism of a prosperous civilization, are indicated by the prizes which earnest Americans offer for the t heoretical abolishment of evil, and the theoretical upbuilding of good.

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.