A RESPONSIBLE if somewhat sectionally slanted journal was commenting on a controversial decision of the Supreme Court of the United States. “The most sacred and binding compacts of former years,” it growled, “were annulled to make way for it; and the judicial department of the government was violently hauled from its sacred retreat, into the political arena, to give a gratuitous coup-de-grâce to the old opinions and the apparent sanction of law to the new dogma.” And in a later issue: “Whatever the . . . judges of the Supreme Court may seek to maintain, they cannot upset the universal logic of the law, nor extinguish the fundamental principles of our political system.”

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. This was not a Southern newspaper or magazine protesting the anti-school-segregation decision of 1954. It was New England’s own Atlantic Monthly, protesting early in 1858 the Dred Scott decision.

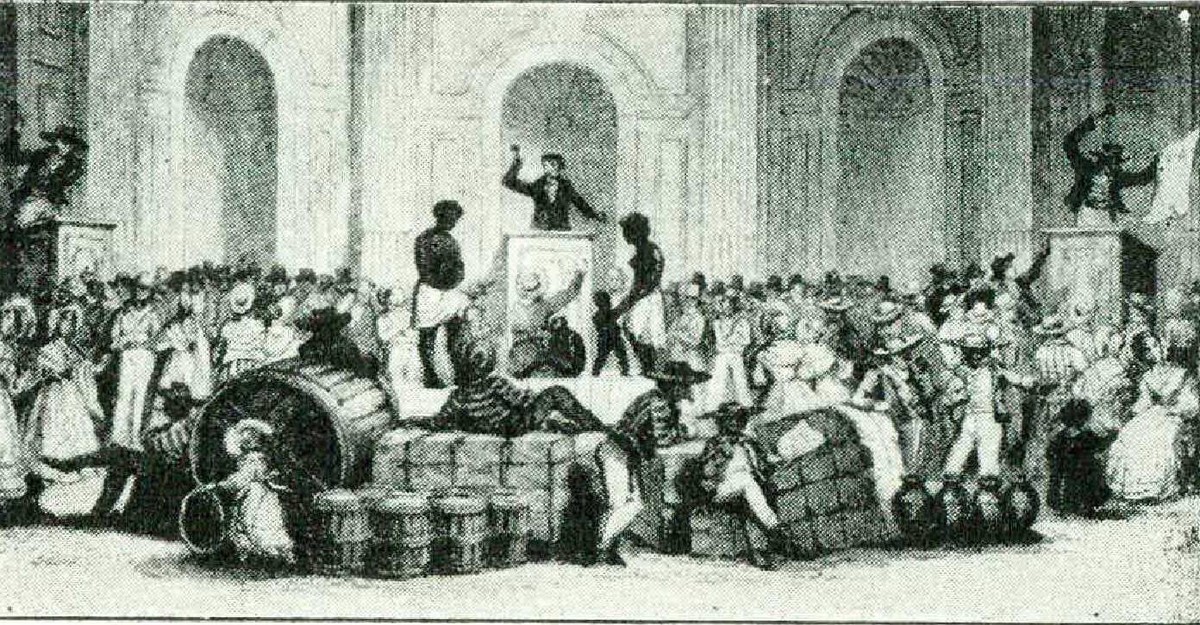

The Dred Scott case of 1857 is the most famous — or notorious — in all of our judicial history. It is the only one that every schoolboy knows by name, though rarely by its full name, which was Dred Scott v. Sandford. It is the only one that helped bring on a major war. It is one of only three decisions in 168 years of Supreme Court annals that were eventually reversed, not by the Court itself, not even, legally speaking, by war, but by amendment of the Constitution. (The other two were Chisholm v. Georgia, a minor insult to state sovereignty reversed by Amendment XI, and the Pollock income-tax case of 1895 reversed by Amendment XVI.) And when the anti-segregation ruling of three years ago was called by several commentators “a second Dred Scott case,” they did not mean to lump together, ideologically, the Court’s greatest anti-Negro and pro-Negro decisions; the metaphor merely put the new case beside the old at the pinnacle of political importance.

Yet, for all the familiarity of its name and of the bare fact that it bestowed judicial blessing on the institution of slavery, the full story of the Dred Scott case is not widely known, even among lawyers. Indeed, the off-stage scenario did not come to light until well into the twentieth century, when the papers of President Buchanan and, later, of Justice McLean were published. Had that story been contemporarily known, the newborn Atlantic Monthly might have used still harsher language than it did when it spoke of “a Court whose members are selected, not for uprightness of character or breadth of mind, but by the inverse test of their capacity for cringing subservience to party.”

For, when else has the Supreme Court been chivvied into making a major and explosive political pronunciamento out of a case it could have handled, and originally planned to handle, on a mild and minor ground — chivvied by the declared intent of one Justice, who was ope

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.