Ever since Gertrude Stein made her remark about the Lost Generation, every decade has wanted to find a tag, a concise explanation of its own behavior. In our complicated world, any simplification of the events around us is welcome and, in fact, almost necessary. We need to feel our place in history; it helps in our constant search for self-identity. But while the Beatniks travel about the country on the backs of trucks, the rest of us are going to college and then plunging — with puzzling eagerness — into marriage and parenthood. While the Beatniks are avoiding any signs of culture or intellect, we are struggling to adapt what we have to the essentially nonintellectual function of early parenthood. We are deadly serious in our pursuits and, I am afraid, non-adventurous in our actions. We have a compulsion to plan our lives, to take into account all possible adversities and to guard against them. We prefer not to consider the fact that human destinies are subject to amazingly ephemeral influences and that often our most rewarding experiences come about by pure chance. This sort of thinking seems risky to us, and we are not a generation to take risks. Perhaps history will prove that we are a buffer generation, standing by silently while our children, brought up by demand-feeding and demand-everything, kick over the traces and do startling things, with none of our predilection for playing it safe.

Our parents kicked over so many traces that there are practically none left for us. That is not to say, of course, that all of our parents were behaving like the Fitzgeralds. Undoubtedly most of them weren’t. But the twenties have come down to us as the Jazz Age, the era described by Time as having “one abiding faith — that something would happen in the next twenty minutes that would utterly change one’s life,” and this is what will go on the record. The people living more quietly didn’t make themselves so eloquent. And this gay irresponsibility is our heritage. There is very little that is positive beneath it, and there is one clearly negative result — so many of our parents are divorced. This is something many of us have felt and want to avoid ourselves (though we have not been very successful). But if we blame our parents for their way of life, I suspect we envy them even more. They seemed so free of our worries, our self-doubts, and our search for what is usually called security — a dreary goal. I think that we bewilder our parents with our sensible ideas, which look, on the surface, like maturity. Quite often they really are, but how did we get them so early? After all, we’re young!

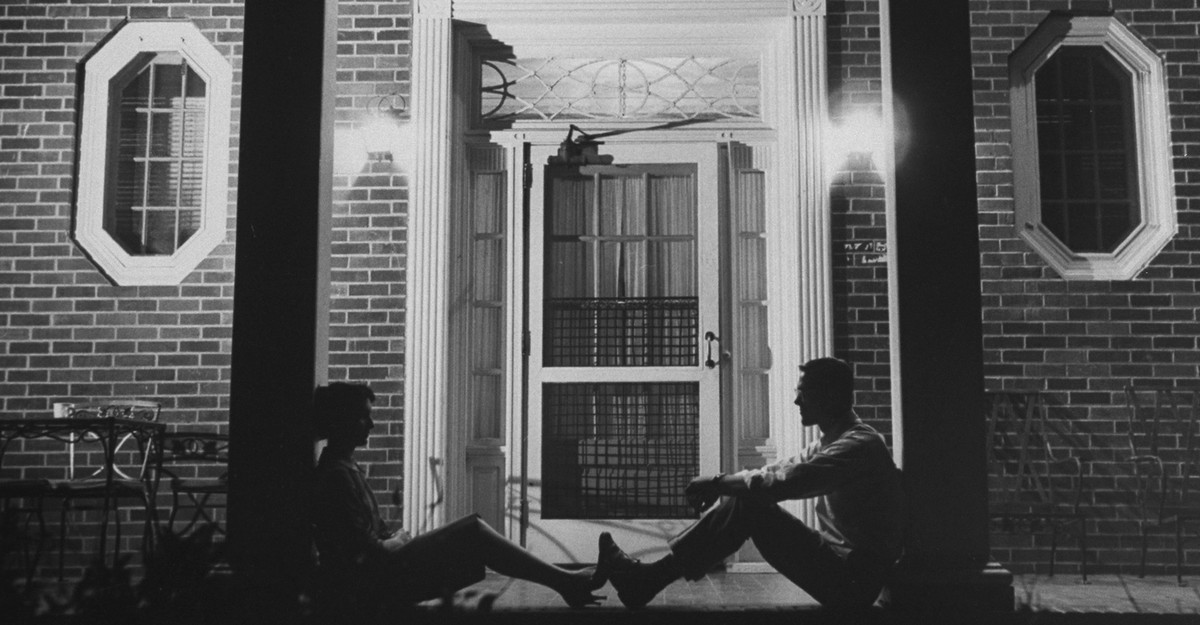

Since so many of us are going to college, a great many of our decisions about our lives have been and are being made on the campuses, and our behavior in college is inevitably in for some comment. Two criticisms rise above the rest: people in college are promiscuous, for one thing, and, for another, they are getting married and having children too early. These are interesting observations because they contradict each other. The phenomena of pinning, going steady, and being monogamous-minded do not suggest sexual promiscuity. Quite the contrary — they are symptoms of our inclination to play it safe.

Promiscuity, on the other hand, demands a certain amount of nerve. It might be misdirected nerve, or neurotic nerve, or a nerve born of defiance or ignorance or of an intellectual disregard of social mores, but that’s what it takes. Sleeping around is a risky business, emotionally, physically, and morally, and this is no light undertaking. I have never really understood why it is considered to be so easy for girls to say yes, particularly to four d

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.