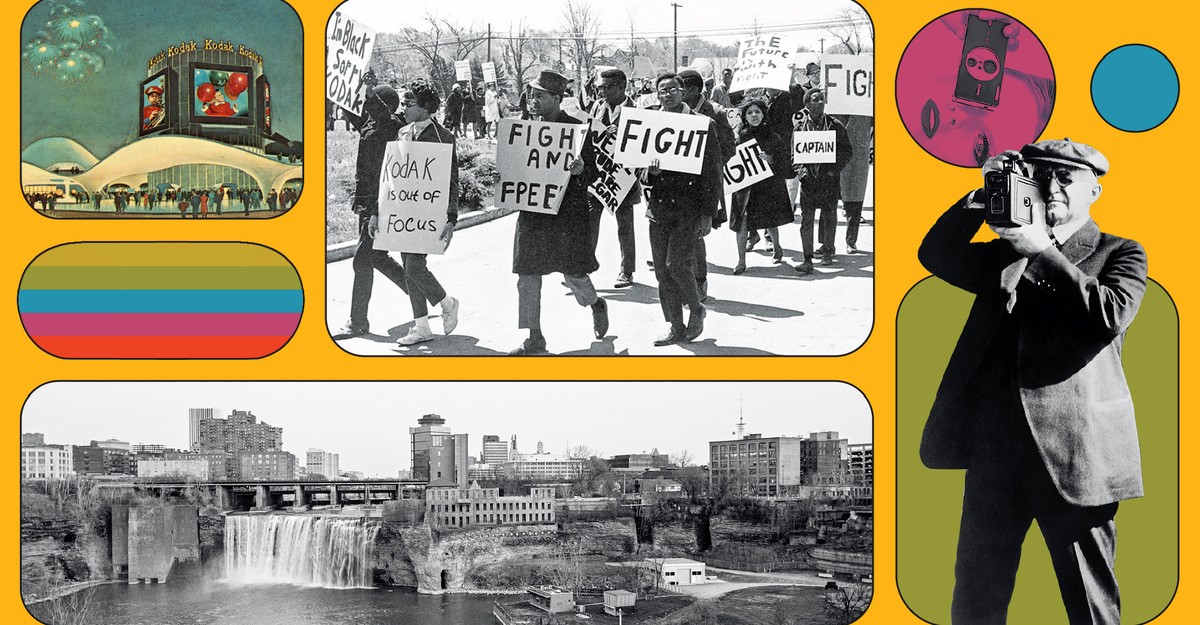

Above, clockwise from bottom-right: Kodak founder George Eastman takes a picture, circa 1925. High Falls in Rochester, New York, Kodak’s hometown. Postcard of the Kodak Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair, 1964. FIGHT, a group seeking to change Kodak’s hiring practices, protests at a shareholders’ meeting, 1967.

This article was published online on June 16, 2021.

When I was in fifth grade, my class took a field trip to the George Eastman Museum, in Rochester, New York, as the fifth graders at my rural elementary school, 30 minutes south of the city, did every year. Housed in a Colonial Revival mansion built for the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company in 1905, the museum is home to one of the most significant photography and film collections in the world. But our job there was to stare at old cameras the size of our bodies, marvel at the luxury of having a pipe organ in your house, and write down what a daguerreotype is to prove that we’d been paying attention. At the end of the tour—in a second-story sitting room full of personal artifacts—we were presented, matter-of-factly, with a copy of Eastman’s suicide letter, dated March 14, 1932: “My work is done. Why wait?” Eastman shot himself in the heart with a Luger pistol at the age of 77.

Telling this story to a bunch of 10-year-olds was not meant to be morbid. It was meant to be edifying: To work is to live. And nobody could argue that Eastman hadn’t worked. His company, founded in 1880, invented the first easy-to-use consumer camera and thereby amateur photography; it achieved a near-monopoly on the consumer-film business, capturing the imagination of the entire world; it was Hollywood, and it was New York, and it was as grand as history—with a simple search, even a child can find images of Eastman hosting Thomas Edison, nonchalantly, in his backyard. The city where we stood was just another of his accomplishments: Eastman funded Rochester’s colleges and its hospital system, its cultural institutions, its nonprofits, its parks, its suburban housing developments. In 1920, his free pediatric dental clinic removed the tonsils of 1,470 children in seven weeks. Even in 2003, when I made that class trip, we were encouraged to believe we should feel lucky that he had chosen Rochester to lavish his attention upon.

Being a child, and having no accomplishments or distinguishing characteristics of my own, I did derive some pride from living near the home of Kodak. My first memories were recorded on Kodak film and developed at the grocery store, and what company could be more important than the company that did that? (I was already pretty convinced of the stunning importance of my personal narrative.) Nobody was offering, but a peek behind the curtain at the company’s sprawling business and manufacturing domain—then called Kodak Park, encompassing 1,200 acres traversed by a private railroad—would have been the equivalent of being allowed inside Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. The only difference was that my own Wonka was dead, cremated, and interred beneath a cylinder of Georgia marble at the factory gates. Also, there would have been no candy.

By the time the offer came, last year, I knew the experience likely wouldn’t be magical. Kodak was already past its prime when I’d visited the Eastman mansion on my field trip, though it reported $4.3 billion in gross profits that year. Since then, many of the buildings in the park had been rented out, sold off, or demolished. The company filed for bankruptcy while I was in college, and rebounded slowly: In 2019, Kodak reported just $182 million in profits. Still, I’d read a few news items about Kodak “pivoting”—a funny word that makes spinning sound intentional—to pharmaceuticals, and as a journalist and an adult, I now had my chance. I’d emailed and asked to hear the story, and was almost immediately told that I could come for a quick visit during a pandemic.

For the past five years, Kodak has been easing its way into the pharmaceutical industry, producing inactive filler materials for generic pills. This will be boring to explain: The company plans to expand under the banner of its Advanced Materials & Chemicals Division, which will continue producing unregulated “key starting materials” and begin making regulated ones, as well as smaller quantities of active pharmaceutical ingredients. The pandemic—which strained global supply chains for generic drugs—prompted a realization from CEO and Chair Jim Continenza, who saw a moment for Kodak to “kind of reinvent ourselves.”

That would require an investment in both jobs and building upgrades, which is why Kodak applied for a $765 million loan through the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation—a federal agency that in ordinary times funds projects only in the developing world. Under the Defense Production Act loan program, and in the context of the pandemic, the year 2020 qualified as nonordinary times, and Kodak’s project qualified as an opportunity for the federal government to do something about the nation’s reliance on overseas manufacturers for generic drugs. Given the draw of Kodak’s name and the low-key bizarreness of an international-development bank pouring money into a forgotten Rust Belt city, Washington’s willingness to entertain the loan application became a news event, despite its relative irrelevance to essentially everyone’s immediate future.

At the end of our fifth-grade tour we were presented, matter-of-factly, with a copy of Kodak founder George Eastman’s suicide letter: “My work is done. Why wait?”

In July, the agency signed a letter of interest with Kodak, a loose but significant promise preceding a longer process of consideration and due diligence. The national reaction was a mix of frenzy and incredulousness. Kodak’s stock soared, and within 24 hours 79,000 amateur traders had added Kodak shares to their portfolios on the Robinhood app. The Trump administration was eager to take credit for the deal, and the White House trade adviser, Peter Navarro, speculated that the company might have “one of the greatest second acts in American industrial history.” The announcement put Kodak up for analysis by the nation’s business pages in a serious way for the first time in several years, though not every publication took it that seriously: Kodak’s shift to pharmaceuticals was, after all, coming “years after” that of “rival Fujifilm,” Fortune wrote. Incidental to much of the discussion, the move into pharmaceuticals was expected to create about 360 new jobs, mainly in Rochester.

But within days, the deal was on the rocks. In a letter to the Securities and Exchange Commission, Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts requested that the agency investigate Kodak for allegations of insider trading, and pointed to large stock purchases before the official loan announcement and other suspicious activity by Kodak executives, including Continenza. She also noted that Kodak had briefed local news outlets about the loan in advance, without telling them the information was embargoed.

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.