1

WHAT is the United Nations Organization, or UN? What is it not? What may we expect from it? What should we do with it? One finds a lead for answering these questions in the experience of the League of Nations between World War I and World War II.

The League of Nations was the outgrowth of a world-wide moral movement that aimed at supplanting the rule of force with the rule of reason in international relations. Its Covenant pledged the members of the League to settle their disputes by arbitration. Any threat of war was to be regarded as a matter of concern to all. Any member of the League that resorted to war in disregard of the Covenant should ipso facto be deemed to have committed an act of war against all other members. The latter were to enact sanctions to enforce the Covenant of the League. This was termed the system of “collective security.”

However, collective action for collective security was not at all secure. Diplomats, military chiefs, and politicians in all countries were persuaded that international relations not based on force were a dream to which it was impossible to give body, and that peace was merely an insecure state of affairs between two wars.

Consequently the governments that had to operate the League never took seriously the Covenant of the League that pledged them not to resort to war. They never intended to give up their right to wage war—that is, their sovereignty. For Lord Curzon, British Foreign Minister in 1923, the League of Nations was nothing but “a good joke.” For Monsieur Berthelot, for many years Permanent Secretary of the French Foreign Office, it was a “grotesque hoax.”

The Covenant of the League resulted from a compromise between two opposing forces: on the one hand, the will to peace of common men everywhere; and on the other, the prepossessions of diplomats, military chiefs, and politicians. Under this compromise the League became an association of governments that pledged themselves to respect certain principles but reserved the right not to carry out those principles. The provisions of the Covenant were like the Commandment which forbids a man to covet his neighbor’s wife.

The League was not a flesh-and-blood individual endowed with a will and a responsibility of its own. It was what lawyers term a “corporate person” — that is to say, an abstract collective noun like “England,” “France,” “Germany,” “State,” “Church,” “Government,”“Bank,” “Union.” These words have a necessary function in juridical doctrine and practice. But in history and politics they hide the personal responsibility of the flesh-and-blood men who are behind those words.

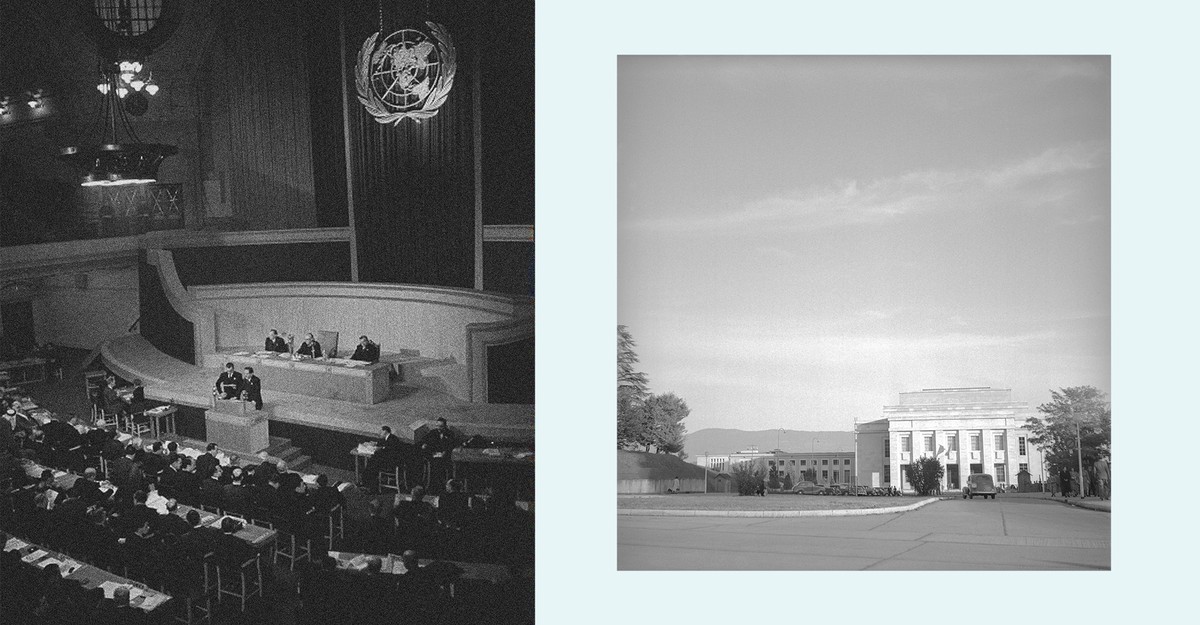

The League of Nations was only what the delegates of the countries that formed it wanted it to be. It was merely a palace in Geneva where diplomats and politicians met to solve problems well, or badly, or not at all, by means of private negotiations. When they had decided what to do or not to do, they met officially in halls called the Hall of the Council of the League, or the Hall of the Assembly of the League, and there they announced their decisions on behalf of the League. Agreements prepared outside the League were laid before the League, and people were told that all had been done by the League. The League, while nothing more than a notary public, was held responsible for everything it was requested to register.

This procedure had conspicuous advantages for diplomats and politicians. When a problem had been solved satisfactorily, they took credit for the good solution. When the problem had been badly settled, or not settled at all, the fault was ascribed to the League. In 1923, the French and British Foreign Ministers, instead of putting down Mussolini when he wantonly seized Corfu, saved his face through a deplorable compromise. Responsibility for this compromise was saddled on the League.

In 1931, it was not the British Foreign Minister who allowed Japan a free hand in China: it was the Lea

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.