The American military is not supposed to intervene in domestic politics. This is the long-standing norm governing U.S. civil-military relations. The Constitution asserts civilian control over the military, divided between the executive and legislative branches, as a means of preventing the military from becoming a partisan force of domestic oppression.

President Donald Trump has destabilized this arrangement more than any president in recent memory. He has imposed National Guard forces on unwilling governors and mayors on the dubious grounds that American cities are more violent than battlefields in Afghanistan. He has invoked laws designed to limit the domestic use of the military—the Insurrection Act, for example—for the opposite purpose. And he has openly encouraged military partisanship, such as when he held political rallies with military audiences at Fort Bragg and Naval Station Norfolk, encouraging them to cheer his disparagement of Democratic governors.

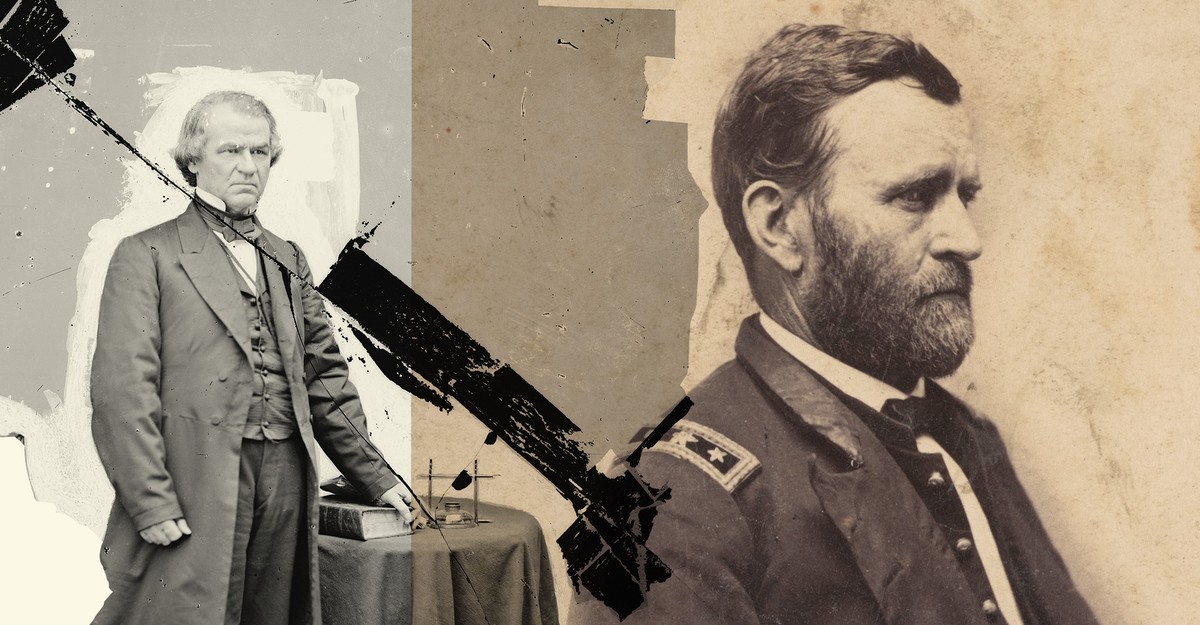

The last time the American military found itself under anything close to this kind of political pressure was during the constitutional crisis of 1866–67. At that time, Ulysses S. Grant was the commanding general of the U.S. Army. The Civil War had recently ended, and President Andrew Johnson faced monumental decisions: On what terms would his administration allow the readmission of Confederate states to the Union, and what civic and economic roles would Black Americans play in the antebellum South? Even as the administration struggled to bring the conquered southern states under its control, an insurgency took root there, terrorizing Black citizens, Republicans, a

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.