Lisa Fagin Davis was starting her medieval-studies Ph.D. at Yale in 1989 when she got a part-time job at the university’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library. Her boss was the curator of early books and manuscripts, and he stuck her with an unenviable duty: answering letters from the cranks, conspiracists, and truthers who hounded the library with questions about its most popular holding.

In the library catalog, the book—a parchment codex the size of a hardcover novel—had a simple, colorless title: “Cipher Manuscript.” But newspapers tended to call it the “Voynich Manuscript,” after the rare-books dealer Wilfrid Voynich, who acquired it from a Jesuit collection in Italy around 1912. An heir sold the manuscript to another dealer, who donated it to Yale in 1969.

Explore the September 2024 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

Davis grew up in Oklahoma City, transfixed by the fantasy worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien and Dungeons & Dragons. When the Beinecke curator first showed her the Voynich Manuscript, she thought, This is the coolest thing I’ve ever seen.

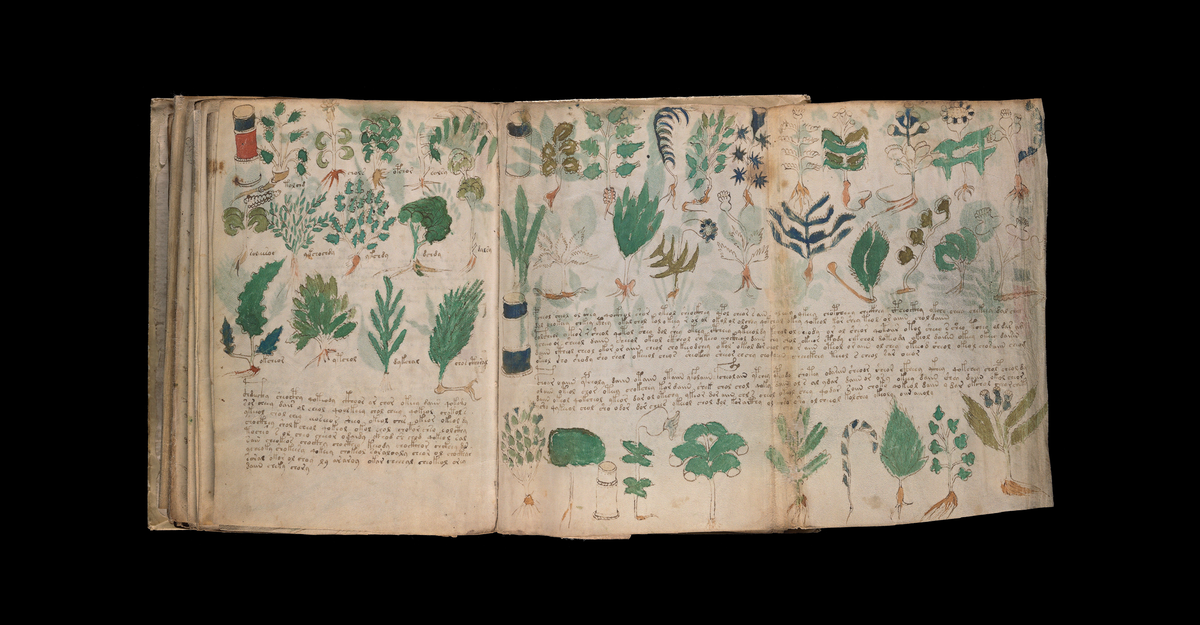

Its 234 pages contained some 38,000 words, but not one of them was readable. The book’s unnamed author had written it, likely with a quill pen, in symbols never before seen. Did they represent a natural language, such as Latin? A constructed language, like Esperanto? A secret code? Gibberish? Scholars had no real idea. To Davis, however, the manuscript felt alive with meaning.

Flowering through the indecipherable script were otherworldly illustrations: strange, prehistoric-looking plants with leaves in dreamy geometries; oversize pages that folded out to reveal rosettes, zodiacs, stars, the cosmos; lists of apparent medicinal formulas alongside drawings of herbs and spindly bottles. Most striking of all were the groups of naked women. They held stars on strings, like balloons, or stood in green pools fed by trickling ducts and by pipes that looked like fallopian tubes. Many of the women, arms outstretched, seemed less to be bathing than working, as plumbers in some primordial waterworks.

Although the book’s parchment and pigments looked medieval, the drawings of the women had no close cultural parallel, in any era. Even the plants—which appeared to have the stems of one species and the roots of another—resisted identification.

Davis, then 23 years old, with a rosy sense of the world’s knowability, wanted to figure out what the Voynich Manuscript was, what it meant, where it came from. But people in her field saw the Voynich as a waste of time, a house-of-curiosities gewgaw unworthy of the serious scholar, especially when so many legible manuscripts begged for study.

From the June 2020 issue: Ariel Sabar on a biblical mystery at Oxford

In any case, scholars had already tried. The manuscript had reeled them in with what one cryptanalyst called a “surface appearance of simplicity”: letters that looked glancingly Latin, words that repeated with language-like regularity, handwriting that had the easy flow of a long-established script. But Renaissance-era intellectuals, Ivy League professors, and spy-agency code breakers—including William Friedman, who cracked Japan’s World War II “Purple” cipher before becoming the National Security Agency’s chief cryptographer—all toiled in vain to unlock the Voynich’s secrets. So many headline-making “solutions” had been debunked over the years that the text had earned a reputation, in the words of a Beinecke librarian, as “the place where academic careers go to die.”

Read: “Pure poison” for a scholarly career

For all anyone knew, the manuscript was nothing more than the ravings of a lunatic, or a hoax to dupe some fool into paying a fortune for it. In his magisterial history of code breaking, the writer David Kahn called the Voynich “the longest, the best known, the most tantalizing, the most heavily attacked, the most resistant” of cryptographic puzzles. H. P. Kraus, the dealer who donated the manuscript to Yale, once likened it to the mythical Sphinx, “its lair strewn with the bones of those who failed to solve the riddle, and still awaiting the Oedipus who will give the right answer.”

To the aspirants who wrote to the Beinecke, Davis sent minimalist replies: prints, from microfilm, of whatever pages they requested, without comment. The Beinecke got more than enough attention from unstable-seeming “Voynich people.” Davis was careful not to encourage them, or to betray her own fascination. When she began checking out books on the manuscript—to feed her own curiosity—she didn’t tell her boss, a medievalist who would soon become her dissertation adviser. “What I wanted more than anything,” she told me, “was for him to respect me.” But the further along she got in graduate school, the less she thought about the Voynich, until she scarcely thought of it at all. If her field saw the manuscript as beneath its dignity, then perhaps she should too.

I met Davis in Boston this past March, some 35 years after her youthful infatuation with the manuscript.

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.