When Thomas Jefferson was chosen to draft the Declaration of Independence, he had an exceedingly difficult task ahead of him. The 33-year-old planter, who had left law practice just before Britain’s imperial crisis began in earnest, needed to do nothing short of lay the groundwork for a new nation. He had to explain in both philosophical and legal terms the Second Continental Congress’s decision to break away from Great Britain, provide a list of grievances against the Crown that justified complete separation as a remedy, and plant the seeds of diplomacy for the fledgling country. His job was to place the newly formed United States of America among “the powers of the earth.”

Explore the November 2025 Issue Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read. View More

In the course of writing a document capacious enough to do all of that, Jefferson formulated the Declaration’s second paragraph, with language that has become its most quotable passage: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Those words, now held as perhaps the world’s most important statement of universal human rights, were so powerful that they are often described as the “American creed.”

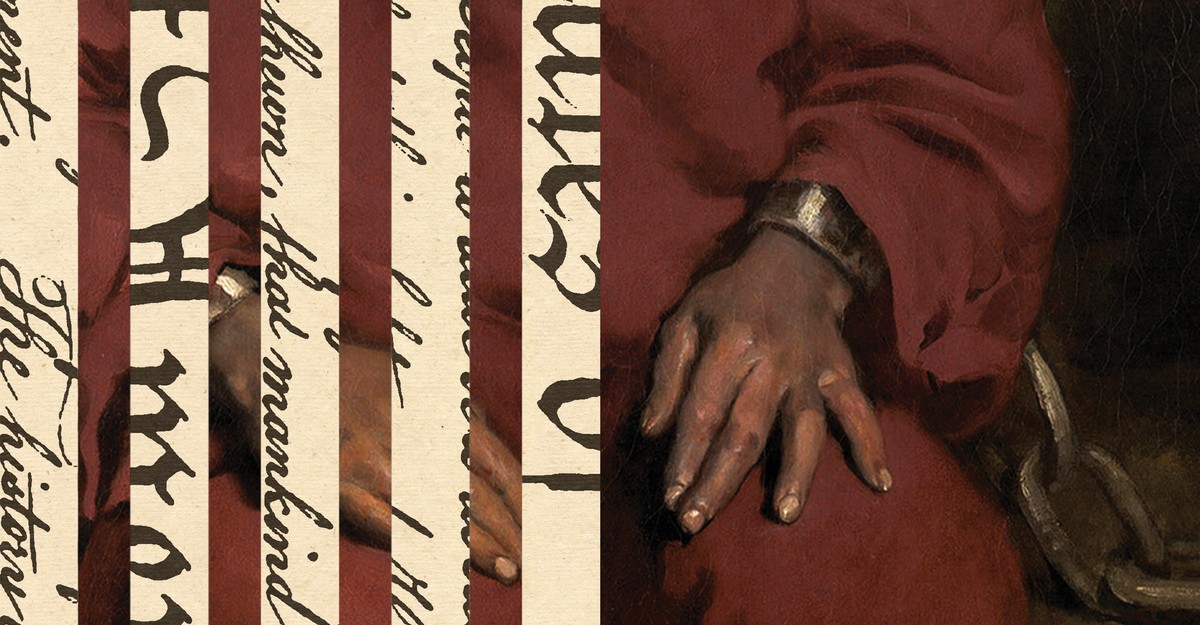

But those words also created a glaring contradiction. Of the estimated 2.5 million people living in the American colonies, about 500,000 were enslaved people of African descent, the majority of whom lived in the southern colonies. About 200,000 lived in the largest colony, Jefferson’s Virginia. At the time Jefferson wrote that part of the Declaration, he owned nearly 200 people at his home plantation, Monticello, and other sites. While working on the document in Philadelphia, he shared rooms with his enslaved valet, Robert Hemmings, the 14-year-old half brother of his wife, Martha.

In the centuries since, Jefferson’s Enlightenment-influenced flourish in the Declaration’s second paragraph has occupied an ever-greater space at the core of American law and culture. Over that period, a question has recurred: Did Jefferson really intend his statement of equality to apply to everyone?

Two hundred and fifty years on, however, it’s time to move past the fixation on Jefferson’s intent. It was never realistic to think that the meaning of a document suffused with revolutionary possibilities could remain within the parameters of Jefferson’s personal beliefs, however we might divine them. Through the exertions of Black Americans and others concerned about progress toward a more just society, the Declaration has been given life and purpose beyond what we take to have been its author’s sight. Perhaps their intentions are what matter most now.

For the substantial number of Americans who have wished over the years to exclude Black people from the polity, Jefferson’s intent has always been paramount. As one argument goes, Jefferson and other members of the founding generation did not think African Americans were equal to white people; therefore, they were not endowed by the Creator with the rights that European Americans claimed in 1776. This particular message has been delivered in the United States in countless ways in everyday life and in powerful venues at crucial moments.

From the June 2021 issue: Annette Gordon-Reed on Black America’s neglected origin stories

Notably, the idea that Black people were simply not part of the Declaration’s “all” was at the center of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Continue Reading on The Atlantic

This preview shows approximately 15% of the article. Read the full story on the publisher's website to support quality journalism.